Following up on my previous post, the lawsuits pertaining to the Alien Enemies Act (AEA) actions against illegal Venezuelan immigrants have a new court decision. The issued judicial opinion seeks to consolidate several court cases which all pertain to the AEA.

A short history of how we got here:

President Trump issued Proclamation 10903 on March 14, 2025, which designated Tren de Aragua (TdA) as an invading force and thus subject to the AEA. The proclamation allowed for instant deportation of any Venezuelan, age 14 or older, who had ties to TdA and was present in the USA illegally.

ICE begins rounding up Venezuelan immigrants and sending them to detention facilities located mostly in Texas.

On March 15, 2025, two planes full of immigrants are sent to El Salvador to be confined in a terrorist detention facility, CECOT.

The biggest news story is that of Abrego Garcia, whose removal was an “administrative error”. Of note: Garcia was not accused of being a member of TdA, but rather MS-13. Most pertinent is that MS-13 is not covered by the proclamation, so his case is being handled separately.

The case of J.G.G. v. Trump is the other big news story, featuring Judge Boasberg, which was the emergency hearing to prevent the planes from departing. The government ignored the motion to stop deportation and the planes took off anyway. This case is ongoing and is a lesson in obfuscation and legal tricks, leading to contempt hearings.

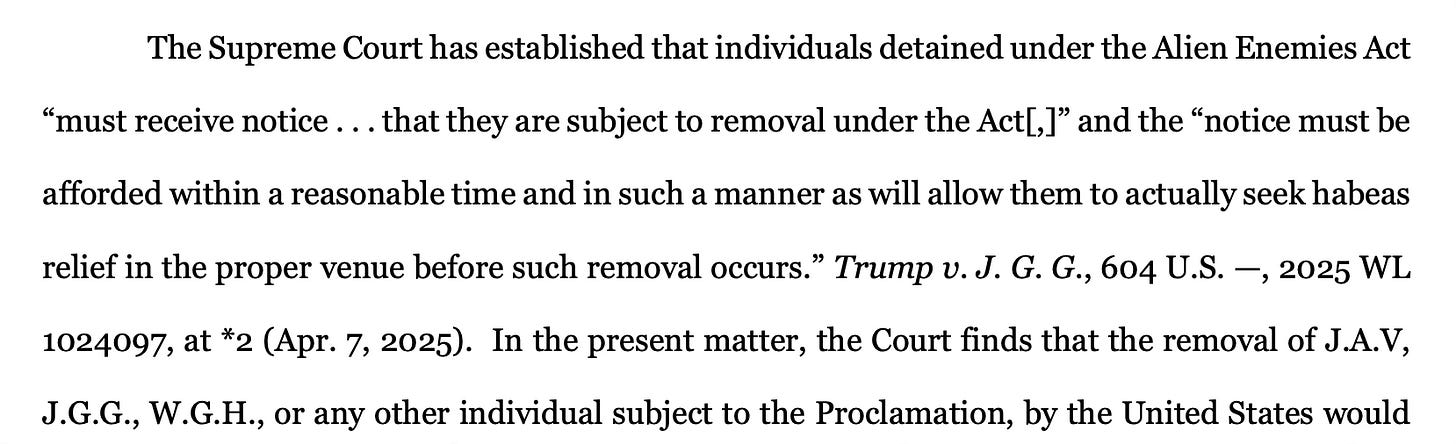

The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, on April 7th, issued guidelines that any removals required written notice, with sufficient time to bring habeas relief proceedings, and that all habeas cases be brought within the District in which they are detained.

Throughout March and April, multiple lawsuits are filed against the government to prevent further deportations.

On April 9, 2025, three Venezuelan men filed a habeas petition and an emergency application for a TRO in the Southern District of Texas to prevent their removal under the AEA, in J.A.V. v. Trump. Judge Fernando Rodriguez granted a TRO that same day preventing any detainees within the El Valle Detention Center from being removed. Several items of note are found in this motion:

Using the Supreme Court J.V.V. decision as a guide, the judge agreed that ANY individual subject to the President’s Proclamation would suffer “immediate and irreparable injury” (i.e. removal from the US) such that they would not be able to seek habeas relief after removal.

The judge also noted that if an individual was removed from the US erroneously, “a substantial likelihood exists that the individual could not be returned to the United States”. This part of the decision directly references the Abrego Garcia case, where the defendants (the government) argued that “a district court lacks the jurisdiction to compel the Executive Branch to return an erroneously-removed alien to the United States”.

The judge granted an extension to the TRO through April 25, 2025.

On April 16, 2025, plaintiffs filed a motion for a preliminary injunction, which the government responded to on April 23, 2025. The plaintiffs responded to this, too. The summary of the motion is telling.

The unprecedented Proclamation at the heart of this case is unlawful because the Alien Enemies Act is a wartime measure that cannot be used where, as here, there is neither an “invasion or predatory incursion” nor such an act perpetrated by a “foreign nation or government.” And even if it could be used against a non-military criminal “gang” during peacetime, targeted individuals must be provided with a meaningful chance to contest that they fall within the Proclamation’s scope. That is particularly so given the increasing number of class members who dispute the government’s allegations of gang affiliation. And the Supreme Court has already ruled that due process requires reasonable notice and the opportunity to obtain judicial review. For these and other reasons, Petitioners–Plaintiffs (“Petitioners”) are likely to succeed on the merits. The remaining factors also decidedly tip in Petitioners’ favor. In the absence of an injunction, the government will be free to send hundreds more individuals, including Petitioners, to the notorious Salvadoran prison where they may be held incommunicado for the rest of their lives. The harm is only magnified by the government’s position that mistakes cannot be remedied, and once an individual is in a foreign prison, they are stuck there. The government will suffer no comparable harm given that the injunction would not prevent it from prosecuting anyone who commits a criminal offense, detaining anyone, or removing anyone under the immigration laws. A preliminary injunction is warranted to preserve the status quo.

So, items of note within the motion, seeking relief under legal justification:

Removal without notice violates due process

Trump’s proclamation does not fall within the statutory bounds of the AEA

The proclamation violates humanitarian protections of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)

Requests class certification for all immigrants that meet the criteria

The government’s response to the motion focused on whether the court had jurisdiction to decide the case, denied that there was insufficient notice given, and defended the decision to classify TdA as an invading force under the AEA.

On April 24, 2025, the judge expanded the TRO to prevent ANY deportations from the Southern District of Texas. The previous TRO only applied to El Valle Detention Center.

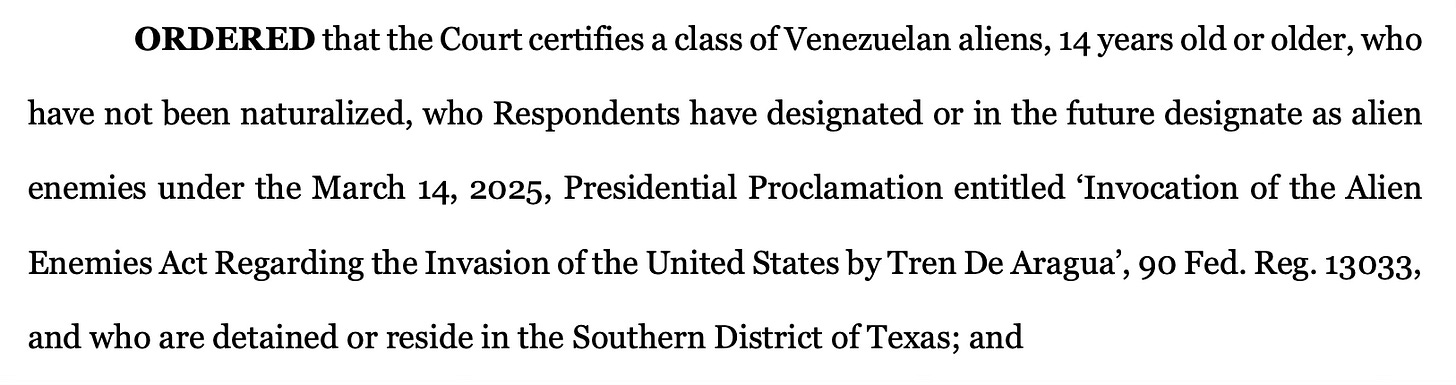

On May 1, 2025, Judge Rodriguez issued two decisions which have potential application to future jurisdictional cases. The first was to grant certification of a class of plaintiffs and the second was to issue a permanent injunction forbidding removal under the AEA of any detainee, present or future, within the class. While I fully expect both decisions to be appealed, likely all the way to the Supreme Court, both decisions are worthy of explanation here.

Class Certification

It is unusual to have a certified class for a habeas proceeding, so the first section of the court’s opinion is devoted to reasoning whether this is permissible. While the Supreme Court has never decided directly as to whether habeas proceedings can be a class action, the Court has heard a few cases where a District Court certified a class but the class certification was not an issue of the appeal. One of the cases cited is Nielsen v. Preap, 586 U.S. 392, which was decided by the Robert’s Court in 2019. Clearly the judge is thinking ahead to this potentially being appealed to the Supreme Court, so citing a case where Justice Samuel Alito wrote the majority opinion gives indication that the certified class will be upheld.

Some Circuit Courts have ruled that habeas actions can apply to a class of individuals. One of the most direct cases to support this is from the 9th Circuit in 1972, Mead v. Parker, 464 F.2d 1108. In this case, 27 prisoners of a federal penitentiary were seeking access to adequate legal materials. Key findings within this decision:

The legal and factual issues affect every indigent inmate who now does or may in the future wish to commence or defend a proceeding in court. It is alleged that there are 500 or more of them. Any relief that might be afforded would benefit them all. … Certainly the usual habeas corpus case relates only to the individual petitioner and to his unique problem. But there can be cases, and this is one of them, where the relief sought can be of immediate benefit to a large and amorphous group. In such cases, it has been held that a class action may be appropriate.

Multiple cases in other Circuits have confirmed this finding. So, the judge concluded that class action can proceed to the evaluation phase, which is found in the US Code Title 28 - Judiciary and Judicial Procedure Appendix Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Content - Title IV. Parties Rule 23 - Class Actions.

Rule 23 requires four conditions: numerosity, commonality, typicality, and adequate representation. We will examine the first three of these in more detail. The last requirement states “the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class”. In this case, the judge determined that this was satisfactory.

Rule 23 (a) (1) “the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable”

Joinder is when two or more parties (or charges) are connected during a court case. This allows multiple issues to be heard at one time, resulting in a more efficient process due to only needing to present the facts once instead of multiple times. Although this case has three plaintiffs, and another case in the Southern District of Texas is also underway, there is no disputing that the number of Venezuelan detainees is fluid due to transfers into and out of the various detention facilities.

At one point, before the ruling in J.G.G. v. Trump, there were over 100 individuals in the Southern District of Texas designated as alien enemies. In supporting documents for J.G.G. v. Trump, there were 86 individuals detained who met the Proclamation requirements, and an additional 172 who had yet to be detained. Although this document does not identify which detention centers contain these individuals, the facts suggest that any or all of these aliens could be sent to a facility within the Court’s jurisdiction.

The Court finds that Respondents have the ability to transfer a significant number of unidentified Venezuelan aliens into the Southern District of Texas, designate them as alien enemies under the Proclamation, and subject them to removal under the AEA. Respondents could utilize detention facilities for these purposes throughout the Southern District of Texas, rendering joinder impracticable due to the geographic dispersion. The fact that these individuals currently remain unknown further precludes their joinder. Thus, the factor of numerosity supports the application of an analogous class-like procedure.

Rule 23 (a) (2) “there are questions of law or fact common to the class”

Members of a class are permitted to have individual issues, yet still be within the class action if they share at least one factor to be adjudicated. The common issues for this case relate to whether the AEA is legally applicable, that they have all been denied due process, and that the procedures used by the government violate both the INA and the Convention Against Torture. While subsequent hearings for individual detainees will have different facts as to proof of TdA status, all cases are common to proceeding under the Proclamation. Thus, this condition is met.

Rule 23 (a) (3) “the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the class”

This requirement is satisfied because all putative class members are subject to the same proceedings under the Proclamation and the AEA. All class members are, and will be, challenging the lawfulness of the invocation of the AEA through the Proclamation.

Because all four conditions for Rule 23 have been met, the judge issued an order that confirmed the class of Venezuelan aliens, age 14 or older, who are not naturalized, and who are designated alien enemies under the AEA. This includes the current plaintiffs and all future plaintiffs who meet these qualifications.

Permanent Injunction

The question that this lawsuit presents is whether the President can utilize a specific statute, the AEA, to detain and remove Venezuelan aliens who are members of TdA. As to that question, the historical record renders clear that the President’s invocation of the AEA through the Proclamation exceeds the scope of the statute and is contrary to the plain, ordinary meaning of the statute’s terms. As a result, the Court concludes that as a matter of law, the Executive Branch cannot rely on the AEA, based on the Proclamation, to detain the Named Petitioners and the certified class, or to remove them from the country.

Because Judge Rodriguez certified the class, the decision rendered by this injunction applies to all members of the class, present and future. The judge begins his opinion with a background of what the AEA is and the history related to it, including circumstances surrounding its creation and review of previous invocations. I covered much the same territory in my prior newsletter about the AEA. The judge then gives a background on what TdA is and the history of the US dealing with its members.

I appreciate the methodical approach of Judge Rodriguez. Mindful that his opinion will likely be appealed, plus noting that there are multiple cases pending in multiple districts, he attempts to cover multiple arguments that have been noted by both sides in an attempt to be thorough. In the first footnote, attached to the summary quote above, Judge Rodriguez notes “Although this conclusion renders it unnecessary to reach all of the challenges that Petitioners present, to facilitate appellate review, the Court reaches some of those other issues.”

Two arguments in the plaintiff's motion concerning due process are dismissed as moot. First is whether being given only 12 hours notice of being classified an alien enemy and then 24 hours to file a habeas motion is sufficient to satisfy a “reasonable time” as stated in the J.G.G. decision. Obviously, the three named defendants DID file a habeas motion, thus why we have this ruling. However, any future plaintiffs may indeed need longer notice periods. But, since the overall ruling of this case pre-empts the circumstances under which notice is needed, this is also moot. In other words, since this ruling declares the AEA cannot be used to detain and deport class members, there is no need to rule on whether due process has been sufficient. The second argument was whether the government should be required to allow time for voluntary departure before detainment and deportation. Because the aliens are identified as being actively hostile, the government need not provide an opportunity for voluntary departure.

The plaintiffs argue that the Proclamation violates the INA and the United Nations Convention against Torture. The Court determined that it did not have the appropriate jurisdiction to rule on the Convention.

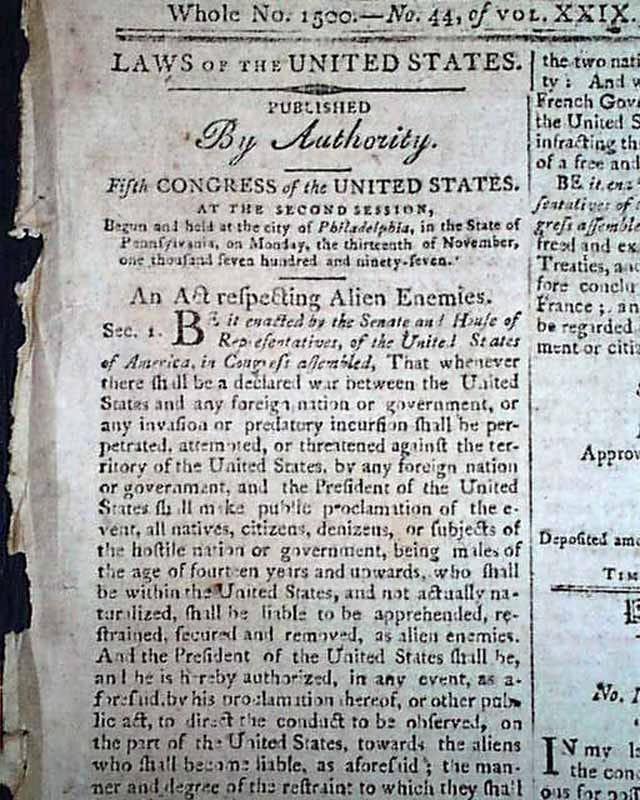

No one disputes that TdA is classified as Transnational Criminal Organization (TCO), nor that they are a real and present danger to the United States. What is at question here is whether the Proclamation meets the requirements of the statute (the AEA). The AEA, 50 U.S.C. § 21 may be invoked by the President only when there is a declared war between the United States and a foreign nation or government.1

This case was brought by habeas action, whereby they are not seeking release from detention, but rather outright removal from the United States. The respondents claim that the court does not have jurisdiction to decide whether the preconditions for invoking the AEA have been met. Rather they claim it to be a political question left for the discretion of the President.

The Supreme Court, in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137, 170 (1803), established the practice of judicial review to determine the constitutionality of laws. It noted that there are some questions that cannot be answered by the judicial branch, and the President has political powers that are at his own discretion. However, the courts do have a right to judge whether discretionary actions are constitutional. In Martin v. Mott, 25 U.S. 19 (1827), the Supreme Court declared “the authority to decide whether the exigency has arisen, belongs exclusively to the President, and that his decision is conclusive upon all other persons”. In a more modern case, Mitchell v. Forsyth, 472 U.S. 511, 541 (1985), Justice Stevens wrote that when the Executive Branch “make[s] erroneous decisions on matters of national security and foreign policy, the primary liabilities are political. Intense scrutiny, by the people, by the press, and by Congress, has been the traditional method for deterring violations of the Constitution by these high officers of the Executive Branch”. So, yes, the President does have the power to invoke the AEA.

Where it gets interesting is under what circumstances a particular alien enemy can petition the courts for relief. There are very few Supreme Court cases which specifically address the AEA, but this case points out those situations. First up is Ludecke v. Watkins, 335 U.S. 160, 164 (1948). Ludecke states that aliens can petition the courts “to challenge the construction and validity of the statute and to question the existence of the ‘declared war’.” Ludecke also affirms that courts can address concerns related to constitutionality and interpretation; also as to whether a declared war actually exists. Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763, 774 (1950) allowed for the courts to address the existence of a war and whether the alien in question meets the criteria of an alien enemy under the AEA. And, recently, under the J.G.G. ruling, the current Supreme Court affirmed “that an individual subject to detention and removal under [the AEA] is entitled to ‘judicial review’ as to ‘questions of interpretation and constitutionality’ of the Act as well as whether he or she ‘is in fact an alien enemy fourteen years of age or older’”.

Since the judiciary is allowed to question the interpretation of a statute, Judge Rodriguez proceeds to do so in a logical fashion. In El-Shifa Pharm. Indus. Co. v. United States, 607 F.3d 836, 856 (D.C. Cir. 2010) affirms “that a case or controversy may involve the conduct of the nation’s foreign affairs does not necessarily prevent a court from determining whether the Executive has exceeded the scope of prescribed statutory authority or failed to obey the prohibition of a statute or treaty”. Even for actions which involve sensitive foreign relations or state secrets, information can always be submitted in camera to preserve confidentiality.

But construing the language of the AEA does not require courts to adjudicate the wisdom of the President’s foreign policy and national security decisions. Determining what conduct constitutes an “invasion” or “predatory incursion” for purposes of the AEA is distinct from ascertaining whether such events have in fact occurred or are being threatened.

Because the invocation of the AEA is left to the power of the President, the factual presentation justifying said invocation cannot be questioned by the courts as it is a political question that is exempt from judicial scrutiny. In other words, although there have been questions as to the accuracy of the facts presented in President Trump’s Proclamation, the court is not permitted to investigate their validity since there are situations that may occur outside the public sphere and only known to the Executive Branch. The court cannot fully assess the accuracy of the facts cited to invoke the AEA.

…the Court concludes that a Presidential declaration invoking the AEA must include sufficient factual statements or refer to other pronouncements that enable a court to determine whether the alleged conduct satisfies the conditions that support the invocation of the statute. The President cannot summarily declare that a foreign nation or government has threatened or perpetrated an invasion or predatory incursion of the United States, followed by the identification of the alien enemies subject to detention or removal.

Judge Rodriguez proceeds to determine the statutory meaning behind “invasion”, “predatory incursion”, and “foreign nation or government”. Following typical rules for judicial interpretation, words contained within statutes are to be interpreted according to their meaning contemporaneously to when they were written. Thus, both invasion and predatory incursion reference military-type actions from an organized, armed force. He does note that neither term is required prior to declaration of war.

Thus, while the Court finds that an “invasion” or “predatory incursion” must involve an organized, armed force entering the United States to engage in conduct destructive of property and human life in a specific geographical area, the action need not be a precursor to actual war.

In determining whether a foreign government is behind TdA, the Court found that, based on the facts as stated in the Proclamation, the Venezuelan government is indeed controlling the actions of TdA within the borders of the United States. Again, the court is not permitted to assess the accuracy of the facts but must accept them at face value as stated.

However (this is the important bit), the nature of the activities of TdA within the United States DO NOT meet the common meaning of “invasion” or “predatory incursion”. The activities by TdA do harm the American people, but they do not rise to an organized military-type action.

The Proclamation makes no reference to and in no manner suggests that a threat exists of an organized, armed group of individuals entering the United States at the direction of Venezuela to conquer the country or assume control over a portion of the nation. Thus, the Proclamation’s language cannot be read as describing conduct that falls within the meaning of “invasion” for purposes of the AEA. As for “predatory incursion,” the Proclamation does not describe an armed group of individuals entering the United States as an organized unit to attack a city, coastal town, or other defined geographical area, with the purpose of plundering or destroying property and lives. While the Proclamation references that TdA members have harmed lives in the United States and engage in crime, the Proclamation does not suggest that they have done so through an organized armed attack, or that Venezuela has threatened or attempted such an attack through TdA members. As a result, the Proclamation also falls short of describing a “predatory incursion” as that concept was understood at the time of the AEA’s enactment.

Therefore, the President has exceeded the scope of the statute, and the government is prohibited from using the AEA to detain, transfer, and/or deport any aliens that meet the criteria for the class. This ruling does not preclude the government from proceeding against anyone from the protected class using any other reasoning, such as the INA.

Whew! A victory that clears a little of the fog away, but still a long way to go through the appeals process and also within other districts.

Interestingly, I had not seen discussion of the three sections which follow the primary AEA statute. 50 U.S.C. § 22 which allows for the alien to have time to settle his affairs before departure, in a “reasonable time as may be consistent with the public safety, and according to the dictates of humanity and national hospitality”. 50 U.S.C. § 23 speaks to the courts giving “a full examination and hearing on such complaint, and sufficient cause appearing, to order such alien to be removed out of the territory of the United States”. 50 U.S.C. § 24 grants authority to the marshals, or their deputies, “or other discreet person” to remove the alien enemies. I don’t know about you, but ICE is anything but discreet! I was pleased to see that the opinion in this case did take into account these sections.