In January 1770, the HMS Endeavour, commanded by Lt. James Cook, from the Royal British Navy, sailed towards the coast of New Zealand on a voyage of discovery. In the distance he saw a mountain “of prodigious height and its top cover’d with everlasting snow”. He dubbed this peak as ‘Mount Egmont’ after the Earl of Egmont, first Lord of the Admiralty. Mount Egmont persisted on published maps of New Zealand until the early 20th century, when a push was made to restore original Maori names. But it wasn’t until 1985 that the mountain was restored to its original name, Taranaki, but controversy persisted even into the early 2000’s.

This story is not unique. The British Empire consistently created its own names for places without consultation with the local population. You only need to look at names such as Victoria to see a heavy influence of Britain exploration and conquest. The United States was not immune to this process. Throughout westward expansion, as the indigenous populations were displaced, the names of natural features became more “Americanized”. Such is the case with Denali/McKinley.

So that there is a unified way to make maps (and so people don’t get confused), place names [within the United States] are standardized by the US Board on Geographic Names, which falls under the US Geological Survey, the agency responsible for making maps. Renaming a place starts locally and works its way upward to the national level. Each state has a different process in place, but to get final, nationwide, approval goes through the US Boad on Geographic Names. The Board then solicits additional input if needed and can choose to approve, decline, or just let it languish in limbo.

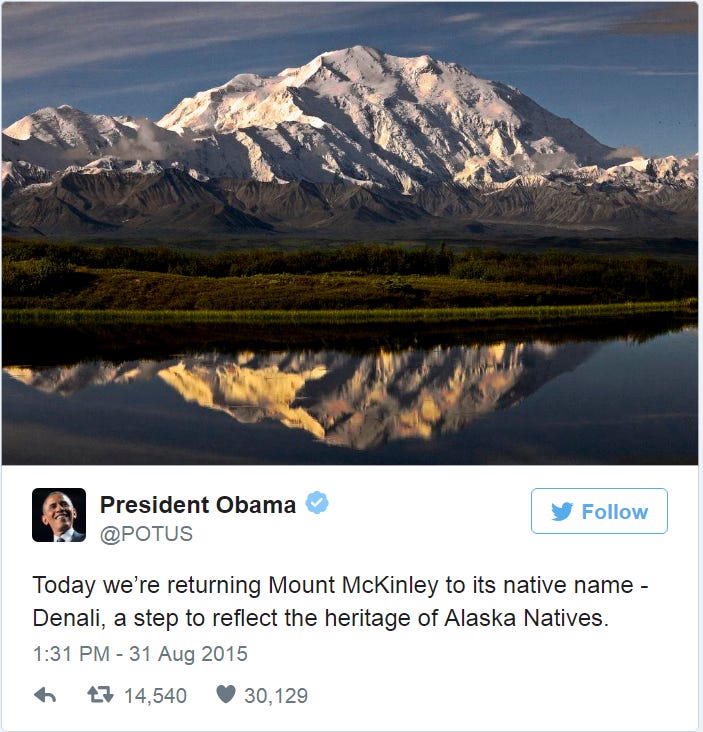

Denali has been an important, sacred site to Alaskan Natives for generations. The mountain was named for McKinley in the late 1800s. The state of Alaska switched the name back to Denali in 1975 and filed paperwork with the US Government’s Board on Geographic Names, where it languished for decades, primarily because Ohio congressional delegates objected to renaming since McKinley was from Ohio. The Department of the Interior oversees the USGS, which oversees the Geographic Name board. In 2015, Secretary for the Interior, Sally Jewell, used a discretionary law which grants authority to change the name if the paperwork has not been acted upon within a reasonable time.

With Trump’s Executive Order 14172, the name change is being reversed. However, this is being done by fiat, not by citizens petitioning through the appropriate methods. Back in 2015, the renaming was just finalizing the process completed since 1975. Already, the Alaskan Congressional Delegates have objected to this name change. We shall see how this all shakes out eventually.

Although many Americans may shrug and say “so what?” to something they perceive as a minor quibble, names matter very much to some, especially those whose identities have been pushed aside or erased.

As our world has become more intricately and instantaneously connected, place names are starting to slowly reflect the rich cultural heritage associated with natural features. Mountains are the easiest to see this reflected, but not always the case. The most famous, highest peak is Mount Everest, named after Sir George Everest who surveyed India for the British Empire. But how many know the Nepali name, Sagarmatha, “Forehead of the Sky”? Or the Tibetan name, Chomolungma, “Goddess Mother of Mountain”?

Many of the most famous mountains throughout the world do indeed reflect on local culture:

Kilimanjaro - combination of Swahili “Kilma” (“mountain”) and KiChagga “Njaro” (“whiteness”)

Elbrus - from Iranian mythology

Puncak Jaya - Sanskrit “victorious mountain”

Kangchenjunga - Lhopo “five treaures of the high snow”

Lhotse - Tibetan “south peak”

Nanga Parbat - Sanskrit “naked mountain”

Pico de Orizaba - Nahuatl “star mountain”

Popocatepetl - Nahuatl “smoking mountain”

Where there is no clear native preference, perhaps due to remoteness or lack of native settlements, other methods have dominated. Names after famous people, e.g. Mount Logan (Canada), Vinson Massif (Antarctica), and Mount Foraker (Alaska); or names after characteristics, e.g. Mount Terror, Cloudripper, and Bandersnatch. The second most famous tall peak, K2, was simply a designation for a label and number corresponding to the first survey, and it has no given local name due to its remoteness. The name has persisted over the years.

Renaming the Gulf of Mexico is not as straightforward as mountains because the name impacts multiple countries, indeed the whole world. While the US Board on Geographic Names could indeed update the name to “Gulf of America” on US maps, there is no governing international body of geographic nomenclature. The United States can request other countries to honor their wishes, but nothing compels them to do so. Typically, most countries use names that are considered the most widely recognized. The ‘simple’ act of renaming can be a performative or symbolic act of power divorced from cultural or practical significance, and can indeed create tensions between bordering nations. For international bodies of water, the International Hydrographic Organization helps to resolve disputes over names, but has no legal authority to enforce nomenclature. Disputes over names of bodies of water are ongoing throughout the world, e.g. Persian Gulf (Iran) v. Arabian Gulf (Saudi Arabia); Sea of Japan (Japan) v. East Sea (South Korea).

The indigenous names for the body of water along the coast of Mexico and the USA were Chalchiuhtlicueyecatl (Aztec) and Naha (Mayan). Spain sent the earliest European explorers to this region; Hernan Cortés was ostensibly the most famous of them and named this body of water “Golfo de Cortés” to symbolize his conquering of Mexico (New Spain). Early maps from the 16th century labeled this water as “Seno de Mejicano” (“Mexican sound”). The first known English labeling, in 1586, was drawn by the Italian cartographer Baptista Boazio, depicting the journey of Sir Francis Drake along the Baye of Mexico. Thereafter, the widespread use was Gulf/Baye of Mexico. As English nautical charts became more prevalent, the body of water was labeled as “Great Gulf of Mexico”, “Ensenada Mexicana’“ (Mexico cove), and Gulf of Mexico. The latter name became, by far, the most common designation, especially as the French Jesuit priests started using this name in 1672.

The United States and Mexico have long had agreements as to jurisdiction, exclusion zones, and borders within the Gulf of Mexico. Starting in 1976, these were formalized such that neither country could exert jurisdiction or sovereignty over the opposite country’s maritime boundaries. To change the name throughout the world, the United States and Mexico would need to come to an agreement, as the two countries with the longest coastline bordering the Gulf, roughly 40% each. Additionally, Cuba also shares boundaries within the Gulf and giving them a say in the renaming would be good diplomacy.

The world will likely continue to refer to this body of water as it pleases, without regard for the wishes of the United States. The ramifications of Executive Order 14172 on the world stage have yet to fully play out, but two items highlight conflict and possible over-reach of the United States attempting to bend the world to its will.

The Associated Press has been banned from the Oval Office and Air Force One because they refused to change their international style guide to reflect the name change. AP believes this to be an abridgment of their 1st amendment rights. The lawsuit hearing is scheduled for March 20.

Mexico is demanding Google reverse the name change.

Interestingly, NOAA still uses Gulf of Mexico on their interactive map.

COST TO TAXPAYER?

There is limited discussion online as to the overall cost of implementation. However, as the President’s stated overall goal is to reduce federal bureaucracy and budget, this seems an easy cost to cut. There is the cost of time and manpower to reprogram online government websites and maps, which is non-trivial. New maps must be printed AND distributed throughout the country. Political maps, topographical maps, nautical charts, and dozens of other types of maps need to be updated. Even if the cost to print is less than 50 cents each, this still encompasses thousands of dollars of taxpayer money. And what about the FTE cost of removing the old maps, editing the press files, and putting up new?

Thanks for journeying with me as we proceed onward through the fog.