[Disclaimer: I am not an economist, so these are just my personal thoughts. Except the history parts, those are…history.]

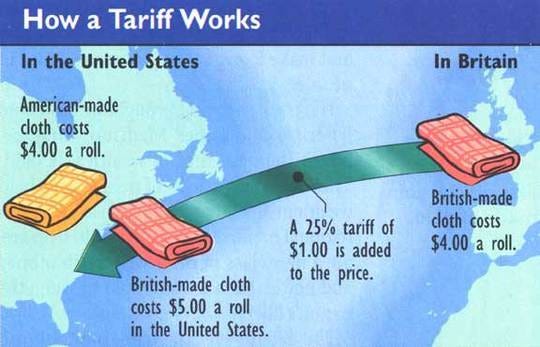

A good starting point for any discussion about tariffs is to define “tariff”. Most people think of tariffs as just an external tax, which is a simple way to approach it. More specifically, a tariff, or duty, refers to a particular tax that is imposed on imported or exported goods. Because of this, tariffs are a way to regulate trade with other countries. In theory, raising tariffs on particular items could make it more economical to buy domestically sourced products, and to promote growth of that industry.

For example, imagine a product is coming into the US at a price of $1000 per ton from country A, and $1200 per ton from country B, vs US domestic price of $1300 per ton. A company here in the US that needs that product to further produce something will likely buy from country A or country B rather than buy domestic because the supply chain is cheaper, therefore the cost to the end consumer will be cheaper, therefore they can potentially take a larger market share. If we impose a tariff on country A of 30% and a tariff on country B of 25%, the total price will be $1300 and $1500, respectively. All other things being equal, it would now be just as economical to use a domestic supplier. You can also provide more favorable rates to countries you prefer. In the given example, a clear preference is shown for domestic or country A and will hurt trade with country B more.

All of this is greatly simplified, but it gets the point across. Tariffs can be used to restrict trade with foreign governments, create preferential supply lines, and promote domestic production. So, tariffs themselves are not a bad thing, as long as they are implemented logically. Yes, the final cost does pass on to the consumer, but, as shown above, if done correctly, domestic sources can benefit enormously.

One thing I learned from my time as R&D in manufacturing is how everything is broken down into cost. When we created a new product, even if very similar to a previous product, we needed to calculate the overall cost using all variables, even down to the electricity cost. So, if our main supply was coming from overseas, we also had to factor in the transport required to get it to the factory and other relevant unseen costs. Transportation cost from Texas to Michigan, usually by rail, costs less than bringing the same supply across from China, and then by rail. When all the costs are properly tallied, the overall cost to the consumer usually only varied by pennies on the dollar.

As I mentioned, I am not an economist, so this simplification is likely to be disputed by those who understand these things better. But my overall conclusion stands that, despite a lot of fear-mongering happening, the cost to us, the consumer, will likely be a lot less than anticipated for most products. There are other reasons to dislike tariffs, such as goodwill with our neighbors, the good of the global economy, lending a helping hand to poverty-stricken nations, etc, but the cost, in my mind, is not the critical argument.

Perhaps the most famous interaction with tariffs dates back to when America was just a British Colony, before the American Revolution. The year is 1765 and Britain imposes the Stamp Act, which was a tax designed to raise revenue for London/Britain by placing a “stamp” on paper-related goods like newspapers and playing cards. The colonists objected saying “no taxation without representation” and it was repealed in 1766. In 1767, Britain tried again with the Townshend Acts, levying tariffs on all sorts of things - paper, glass, lead, tea, paint, etc. Once again, the colonists objected and, soon after the Boston Massacre of 1770, all the tariffs were lifted except on tea.

At the time, the East India Company (EIC) had a monopoly on tea. So the colonists became entrepreneurial and started smuggling in tea, thus avoiding the import duties still in place. The East India Company fell into deep financial trouble. To help them out, Britain allowed them to directly ship to America, bypassing a stop in England. This allowed the EIC to avoid paying tariffs in England and only needing to worry about the tariffs/duty for delivering to America. Basically, instead of being double-taxed, they eliminate a huge cost factor in the price of tea. Thus, this new procedure had the net effect of allowing EIC tea (the “official” tea) to be priced lower than the smuggled tea. Major ports such as New York and Philadelphia refused to let the ships land, so the showdown was set for Boston. Merchants such as Sam Adams, who were profiting from the smuggled tea, realized that if the EIC delivered to America, then, once again, Americans would be subjected to “taxation without representation”. Thus began the plot of the Boston Tea Party of 1773 - for more details on how this developed, read here.

America had its first taste of tariffs, but definitely not the last…

The American Revolution is over, America is no longer a British colony, and our fledgling government is just getting underway. But, how to fund our country? Even with a very small initial government, the United States still needs funds to operate, build up armed forces, start a Treasury, and more. These all take capital to get started and there is no personal income tax at this time. The failure to provide a source of steady revenue is one of the reasons the original Articles of Confederation failed. So, along comes the Tariff Act of 1789. Fun fact, this was the first piece of legislation signed by President George Washington after his inauguration.

James Madison was the sponsor of this Tariff Act, with Alexander Hamilton a proponent, to give our Treasury a kickstart. It was designed to promote trade and to raise revenue to operate the government and to pay back debts incurred during the Revolution. Madison and Hamilton believed, similar to Trump today, that this system would promote American manufacturing in the long term and protect existing manufacturing from being undercut by foreign countries. However, Hamilton also cautioned against using only tariffs to control trade. He authored the Report on the Subject of Manufactures in 1791, which outlined multiple additional avenues to promote domestic production, such as subsidies, import embargoes, and production standards. Importantly, he cautioned against America becoming TOO protectionist and isolationist.

Reading through the original text is quite entertaining as to what is specifically spelled out for tariff imposition. Among the list include:

Madeira wine - 18 cents per gallon

Other wines - 10 cents per gallon

Bottled beer - 20 cents per dozen

Boots - 50 cents per pair

Soap - 2 cents per pound

Twine - 200 cents per 112 pounds

Salt - 6 cents per bushel

Tobacco - 6 cents per pound

Cotton - 3 cents per pound

Tea was broken down into four categories and further broken down by source - English, Indian/Chinese, everything else

A suite of “ad valorem” taxes - these are taxes on luxury items “according to value”, such as coaches, fancy clothing, chinaware, silver, gold, jewelry etc.

Throughout the 19th century, this Act, along with subsequent modifications and additions, proved to be a major source of revenue for the federal government, sometimes as much as 95%. It also served as a method of controlling foreign interactions—hurting nations economically is often far more effective than skirmishes at sea. Thus why imposing sanctions today is still very effective.

Two things to note:

At this point, only Congress had the power to impose tariffs. They would retain control of tariffs until 1922.

Tariffs caused a lot of disagreements, even within the same political party. There also began a rift between the North, more merchants and manufacturing, and the South, more export of cash crops. This would continue to play out for the next 100 years.

Why this dichotomy between the North and South (and later the West)? This goes back to the original explanation of tariffs. The South and West produced mostly crops and were unrivaled in the world and could undercut any sales from imported crops. They didn’t need (or want) protection tariffs. The North needed protective tariffs to guard against cheap foreign goods that would undersell their products (like China today). However, increasing tariffs to protect the Northern manufacturing resulted in retaliatory tariffs in other countries, which would in turn hurt the American farmers who were trying to bring products into those foreign markets. So, tariffs are all about a fine balancing act. Increases in one area result in hurting another area.

Throughout the early 1800’s, several tariff acts were imposed, some more successful than others. All had their proponents and their detractors. Tariffs went up and down multiple times throughout the next 100 years.

Tariff of 1816 - After the War of 1812, cheap foreign goods flooded the US markets, hurting domestic manufacturing. Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun devised the first true protectionist tariff to safeguard American manufacturing interests. Average rates were raised to around 20%.

Tariff of 1824 - rates were again raised, the South is more upset

1828 - “Tariff of Abominations” - Rates were again raised, especially for the textile industry, to protect New England textile mills. The North thought they didn’t go high enough, the West wanted even more duties on raw materials they produced, and the South became even more angry. Nobody was happy.

Tariff of 1832 - rates were somewhat reduced, but not enough to make the South happy. South Carolina was especially angry and sparked the Nullification Crisis.

Sidebar here for Nullification, which is when a state refuses to enforce a federal law within its borders. South Carolina threatened to secede from the Union if the federal government sought to collect on the tariffs. President Andrew Jackson dispatched ships to Charleston harbor and enhanced fortifications. He was fully prepared to go to war. Enter Henry Clay (the same one from the 1816 tariffs) who negotiated with John C. Calhoun (yup, same guy from 1816, now on opposite sides) The Tariff of 1833 was passed by Congress, which would, over the course of 10 years, reduce tariff levels back to 1816 levels. Calhoun agreed and nullification was rescinded. Crisis averted, for now, but both North and South were still unhappy.

America faced a depression brought about by the Panic of 1837, when banks called in their loans. Depositors panicked and began withdrawing their savings. Construction companies failed, unemployment skyrocketed, food riots took place in cities. President John Tyler cancelled the tariff reductions begun in 1833, and signed the Tariff of 1842, which brought rates back up to 1832 levels. His party, the Whigs, were really unhappy with Tyler and attempted to impeach him, but failed.

1846 - Walker Tariff - downward rates, coupled with a move towards revenue only

Tariff of 1857 - downward rates, to almost free trade levels, the North unhappy

Wartime Tariff Acts 1861-1865 - increased protectionism to help fund Union war efforts (South had zero say in Congress since they had seceded)

Tariff rates fluctuated throughout the late 1800’s, highlighted by the McKinley Tariff of 1890 which raised tariffs to 48% and the Dingley Tariff of 1897 which raised some tariffs to 57%.

The year 1913 proved to be an important turning point both for tariffs and for federal revenue. The Sixteenth Amendment passed Congress which gave the federal government the power to levy income taxes. For the first time, the government was no longer heavily dependent on tariffs, and over time it became obvious that income tax revenue far exceeded tariff revenue. President Woodrow Wilson appeared before Congress to persuade them to overhaul the entire tariff structure. The resultant Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act vastly changed the tariff landscape, in a meaningful way, for the first time since before the Civil War. Many items were added to the duty-free listing, especially raw materials, crops, and steel. This had the effect of relieving the stress point that the South and West had felt for many years.

After World War I, America returned to its protectionist ways and the rates soared to extremely high levels once again. The Emergency Tariff Act of 1921 was followed by the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922, which changed the tariff landscape once again. First, this tariff act did something new - it granted the President powers to raise or lower the tariff rates by as much as 50%. A Tariff Commission was created to advise the President. Prior to this, Congress alone had the power to impose tariffs. The new high tariffs made it difficult for Europe to trade with the US, thus impeding the ability to pay off war debts. Retaliatory tariffs came to be imposed, the net result being an almost complete reduction of international trade. An unpredicted side effect of the high protectionist tariffs was the rise of American monopolies in multiple industries.

Thus far, you can see that tariffs have existed throughout US history, and, indeed, have fluctuated widely, up and down. Join me for part II, where things get interesting during the Great Depression and after World War II. Plus we will examine some of the current administration’s tariffs.

History is rarely clear while we move through it, but we can learn a great deal from looking back to shine a light on current circumstances.